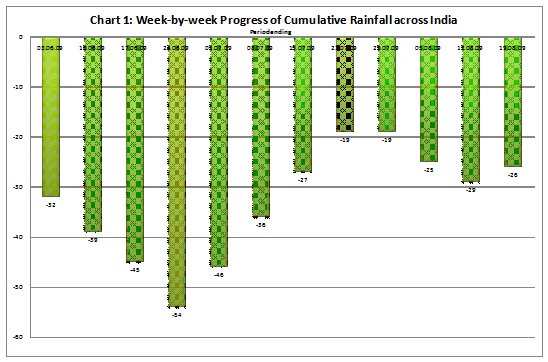

With

just a few weeks to go before the Southwest monsoon

retreats, it seems almost certain that the deficiency

in rainfall would be such as to constitute a drought.

In its press release dated August 21, 2009, the Indian

Meteorological Department declared that rainfall deficiency

relative to the long period average was 26 per cent

over the June 1 to August 19 period (Chart 1). Northwest

India with a deficiency of 37 per cent leads, followed

by Northeast India, Central India and the Southern

Peninsula, in that order. With deficiency having been

high throughout the season in Northwest India and

very high in Central India in the period up to the

first week of July (Table 1), sowing has been delayed

or has not occurred at all. Agricultural output is

thus bound to fall this year.

India last experienced a drought in 2002. The fortuitous

record of six years of normal or good monsoons after

that is now being broken. This is bound to test the

ability of the government to deal with shocks other

than those transmitted through the world of finance.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

As a result of the early drought-like conditions,

on August 13, 2009, area sown under rice was reported

at 247 lakh hectares which is 63 per cent of normal

levels and 19 per cent short of the previous year's

levels. The shortfall relative to the normal was 24

per cent for coarse cereals, 21 per cent for pulses

and 10 per cent for oilseeds. This will obviously

affect aggregate production. The effect is likely

to be significant because kharif production accounts

for around 57 per cent of total crop production.

One crop that is expected to be particularly affected

is rice, which is the most important food crop during

the kharif season. And the impact could be severe

on the marketed surplus of the crop, because some

''surplus states'' have been particularly adversely

affected. The deficiency in rainfall has been high

in those states which contributed a substantial share

of total rice procurement during the marketing season

2007-08. Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and

Chattisgarh, which contributed close to three-fourths

of all rice procured during the 2007-08 marketing

year, have thus far experienced a deficiency in rainfall

varying from 30 to 60 per cent (Table 2).

With the fall in output likely to push up market prices

it can be expected that farmers would prefer to sell

in the market, where prices are likely to be higher

than the floor set by the minimum support price. In

the event, procurement is likely to be low, while

demand from the public distribution system is likely

to rise in the wake of an increase in market prices.

If stocks with the government deplete, this could

trigger speculation based on inflationary price expectations,

setting off a price spiral.

Table

1: Week by week progress of cumulative seasonal

rainfall |

Period

ending |

Country

as a whole |

Northwest

India |

Central

India |

South

Peninsula |

North

East India |

03.06.09

|

-32 |

-40 |

-50 |

-14 |

-32 |

10.06.09

|

-39 |

-31 |

-56 |

-15 |

-44 |

17.06.09

|

-45 |

-26 |

-72 |

-21 |

-46 |

24.06.09

|

-54 |

-49 |

-73 |

-38 |

-55 |

01.07.09

|

-46 |

-45 |

-59 |

-31 |

-41 |

08.07.09

|

-36 |

-50 |

-40 |

-18 |

-34 |

15.07.09

|

-27 |

-43 |

-15 |

-12 |

-40 |

22.07.09

|

-19 |

-38 |

3 |

-6 |

-43 |

29.07.09

|

-19 |

-33 |

1 |

-15 |

-39 |

05.08.09

|

-25 |

-40 |

-13 |

-18 |

-36 |

12.08.09

|

-29 |

-43 |

-19 |

-23 |

-36 |

19.08.09

|

-26 |

-37 |

-22 |

-20 |

-27 |

Table

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

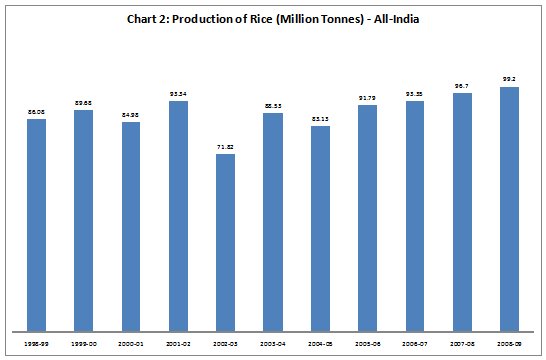

There are three additional reasons why the evidence

of an unfolding drought is a matter for serious concern.

To start with, during the previous drought in 2002,

rainfall was around 81 per cent of the long period

average, as compared with the 74 per cent figure recorded

thus far for this season. Rice production in 2002-03

fell by 23 per cent from its 2001-02 high of 93.34

million tonnes to 71.82 million tonnes. Things could

be much worse this time around. Second, if previous

experience is the basis for prediction, droughts tend

to cluster across time. Thus 2000, 2001 and 2002 all

had below normal monsoon, as did 1985, 1986 and 1987.

If this cycle repeats this could be the beginning

of bad times for the medium term.

Table

2: Share in 2007-08 Rice Procurement and Rainfall

Deficiency Range by State |

|

Share

in Procurement (Oct-Sep) (%) |

Rainfall

Deficiency Range |

Punjab |

27.7 |

36 |

Andhra Pradesh

|

26 |

31-59 |

|

Uttar Pradesh

|

10.1 |

40-46 |

Chhattisgarh

|

9.6 |

30 |

|

Orissa |

8.2 |

4 |

Haryana |

5.5 |

63 |

West Bengal

|

5.3 |

25 |

Tamil Nadu

|

3.4 |

5 |

Kerala |

0.6 |

14 |

|

Maharashtra |

0.6 |

20-50 |

Table

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

Finally, the evidence of drought occurs at a time

when food prices are already high and rising. Going

by annual point-to-point changes in the WPI (relative

to values prevailing a year back), prices on average

have been falling in recent times. After touching

a high peak level in August 2008, largely because

of increases in the prices of oil and other primary

commodities, inflation turned negative in June 2009

and has remained so since then. The figure as on 1

August 2009 stood at a comforting minus 1.74 per cent.

This, of course, is misleading. The annual point-to-point

increase in the monthly CPI for Industrial Workers

stood at 9.29 per cent in June 2009, which is way

beyond the negative 1.2 per cent figure for July yielded

by the WPI. Moreover, the month-on-month inflation

rate as measured by the CPI has been above the August

2008 level in seven of the subsequent ten months.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

The principal reason for the difference between the

WPI and CPI is that prices of different sets of commodities

in the Indian economy have been moving very differently.

Globally, oil prices, though rising, are below the

peak levels they reached sometime back. The prices

of many manufactured goods have also been falling

because of the global recession. On the other hand

the prices of food articles have been rising in recent

times. Thus the Reserve Bank of India's recently released

quarterly review of economic trends had this to say:

''Notwithstanding the negative WPI inflation, food

articles inflation (i.e. primary as well as manufactured)

remains high at 8.9 per cent (as on July 11, 2009).

Inflation as per Consumer Price Indices (CPIs) also

continues at elevated levels (in the range of 8.6

per cent to 11.5 per cent for different consumer price

indices in May/June 2009).''

This raises the question as to the factors behind

the price increase. Production has not fallen. Most

recent estimates place the total food grain production

during 2008-09 at a record 233.9 million tonnes. Stocks

with the government are comfortable. There are enough

foreign exchange reserves in the economy to import

food. And, if anything, demand expansion must have

been dampened by the slowdown in growth in the economy.

To quote the RBI: ''Weakening aggregate demand emerged

as a major constraint to growth in 2008-09.''

However, the dampening effects of the recession on

demand seem to have affected only the prices of non-food

articles and not so much those of food and certain

other essentials. The implications are clear. Speculators

are playing a role in ensuring that prices not only

remain high but continue to rise in a period when

normally they should be in decline. And the fact that

for some time now the wholesale price index has conveyed

the impression that inflation is low and even negative

has rendered the government complacent. There has

been no concerted effort at reining in food prices,

and all attention has been focused on reviving growth.

And monetary policy aimed at responding to the slowdown

in growth is ensuring that speculators are able to

access liquidity quite easily. The danger of high

inflation driven by speculation is only increasing.

Given this context, evidence of a drought is disconcerting

because it can result in an acceleration of food price

inflation with economy-wide consequences, and extremely

adverse implications for the poor. The government

is attempting to talk down inflation and the speculative

surge by pointing to the huge stocks it has at hand

and the country's strong foreign exchange reserve

position that can be used to import commodities in

short supply to hold the price level. But this ignores

the fact that prices of food articles have already

been rising.

It is indeed true that on April 1, 2009 the stocks

of rice and wheat with the government stood at 21.6

and 13.4 million tonnes respectively, as compared

with the official buffer stock requirement of 12.2

and 4 million tonnes respectively for that date. On

May 1 stocks were at an even more comfortable, with

21.4 and 29.8 million tonnes of rice and wheat. Moreover

procurement this season promises to be better than

the last. As on 13 August 2009, procurement of rice

during the 2008-09 marketing season was at 32.5 million

tonnes much higher than the 27.1 million tonnes recorded

during the same period last year.

However, there is the larger question of how the government

would be able to reach this food to areas where it

is most needed, given the woefully inadequate coverage

of the public distribution system in most states.

Since the movement of foodgrains across states and

regions has been liberalised for many years now, this

would affect prices not only in the deficit areas

but elsewhere as well, with traders seeking the best

prices. The government appears to be banking on its

open market sales scheme, or the sale in the open

market at predetermined prices, to dampen prices.

But liberalisation has also increased the role of

private traders including big private players in the

foodgrain market. It is they who would corner these

stocks and hold them till prices do rise. The centre

is attempting to shift the burden of dealing with

the price rise on to state governments. Besides accusing

them of not doing enough to dishoard private stocks,

it is requiring them to organise the distribution

of food. In his speech to a 19th August, 2009 meeting

of Ministers of Food and Civil Supplies of the state

governments, Sharad Pawar, the Minister for Consumer

Affairs, Food and Public Distribution said: ''If required,

Government would not hesitate to undertake open market

intervention and release of wheat and rice under Open

Market Sale Scheme to State Governments. State Governments

should in turn gear up and put in place appropriate

mechanism to sell wheat and rice to consumers and

ensure these releases check inflationary trends in

the food economy.''

The Centre, in its effort to hold State governments

more responsible, is also pressing them to impose

a 50 per cent or more levy on rice millers. With states

not all being in a position to create the necessary

network and handle the distribution process, it is

inevitable that the private sector would be called

in. It is at that stage that the effects of speculation

could intensify necessitating strong action if inflation

is to be reined in.

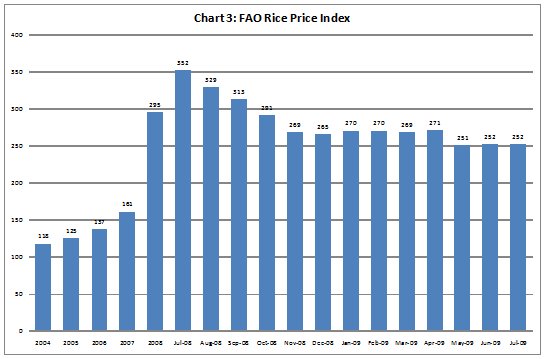

If that happens, the option that would be resorted

to is that of imports. But the situation is not too

favourable in global markets either. The Food and

Agriculture Organisation's Crop Prospects and Food

Situation Report released recently, estimates world

cereal production in 2009 at 2208 million tonnes,

or 3.4 percent down from last year's record harvest.

This is not all bad, since the high base implies that

this would be the second largest crop ever. However,

the situation is less optimistic on the price front.

To consider the case of rice for example, the FAO

Rice Price Index which is based on 16 global rice

price quotations indicates that while prices have

declined from their peak levels of around a year ago,

they are still close to their 2008 high and well above

levels that prevailed in 2007 and earlier (Chart 3).

This, together with the possibility of rupee depreciation

and the difficulty of reaching imported rice to the

final consumer, could imply that even if the government

offers a subsidy, imports may not serve to control

the price level. That may be the cost to be paid for

failing to ensure universal coverage of the PDS, remaining

obsessed with targeting in order to limit food subsidies

and liberalising trade of essentials like food grains.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge